The Global Sand Crisis: Examining Causes, Consequences, and Sustainable Alternatives

Sand is one of the most consumed products on Earth, behind water and air. So, why are we running out and no one knows?

The UN Environmental Program states that, “The 50 billion tons of sand thought to be extracted for construction every year is enough to build a nine-story wall around the planet,” and, sand extraction is only rising more, about 6% each year (UNEP 2023). A multitude of factors contribute to the global sand crisis, from over-reliance on concrete construction to illegal sand mining. This crisis has developed into a multi-faceted issue, concerning social, political, economic, and environmental realms. The shortage revolves around key problems including…

- lack of governing body to regulate sand consumption

- reluctance to divert from concrete usage

- lack of concrete alternatives or viable replacements to sand

- the cyclical nature of the effects of sand mining on coastal and environmental issues

Though diverse, these issues all connect back to the same core issue: the earth cannot replenish sand at the rate we are using it.

On a Small Scale

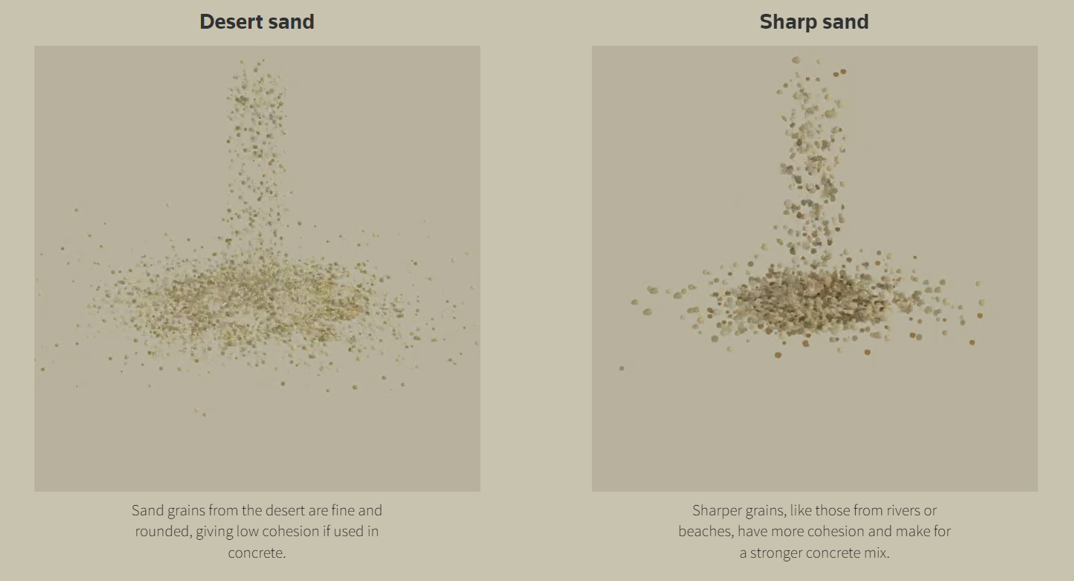

Before diving into these components, it’s important to reflect on sand at a smaller scale and understand how particular factors influence the wider problem. A vast number of products use sand, from microchips and asphalt to windows and building foundations. Sand varies greatly as geographic location heavily influences its quality, shape, and size. In turn, these characteristics determine each type of sand’s ideal use. Specifically, river sand is highly sought after as it is the cornerstone of the construction industry. The sand lining riverbeds has travelled far, from large rocks to miniscule grains of sand tumbled by water and air. Broken apart from those large pieces of sediment, river sand features jagged edges, perfectly suited to grip onto other ingredients of concrete such as Portland cement and admixtures. In comparison to river sand, other sand types have too small of grains or too smooth of edges, leaving them useless for concrete production.

Courtesy of Reuters

The Urbanization Problem

Continuing on, there are additional motivators for using sand and more specifically, utilizing sand for concrete production. Reuters reports that from 2011 to 2013, China used more concrete than the United States used in the entire 20th century. Outside of the US and Europe, labor is cheap and steel is costly, motivating the use of concrete over steel. In India specifically, concrete is not solely chosen for its cost. Rollo Romig writes for the New York Times,

Why don’t Indians just shift to other construction materials? In part it’s because concrete is cheap, strong, easy to use and highly versatile. In part it’s cultural: Building a house out of brawny concrete has come to be viewed by many as a matter of prestige. “They feel that beauty is a beast,” the architect B.R. Ajit told me ruefully. The law encourages this tendency. One environmental lawyer explained to me that the Indian building code recognizes a house as a house only if it’s made from specific heavy materials — concrete included. “If you use that criterion,” he said, “the president’s house is not a house” (Romig 2017)

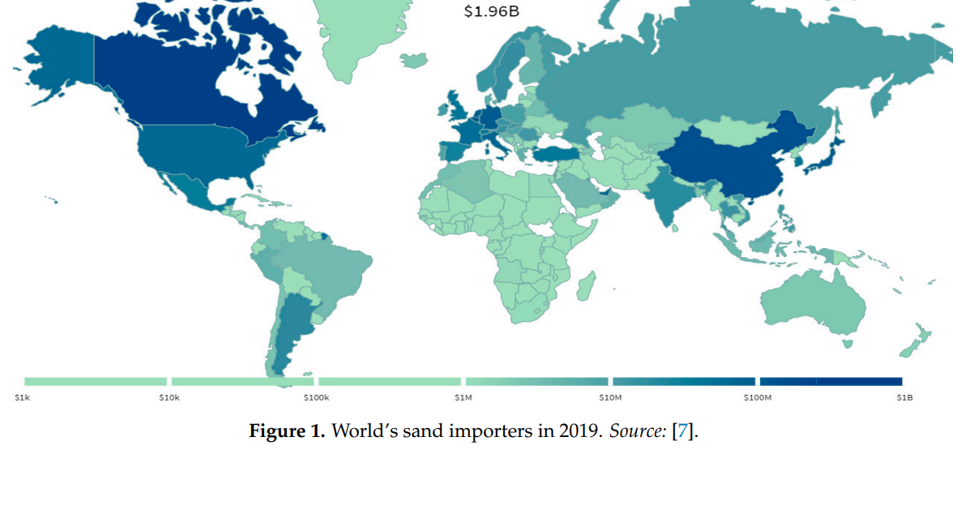

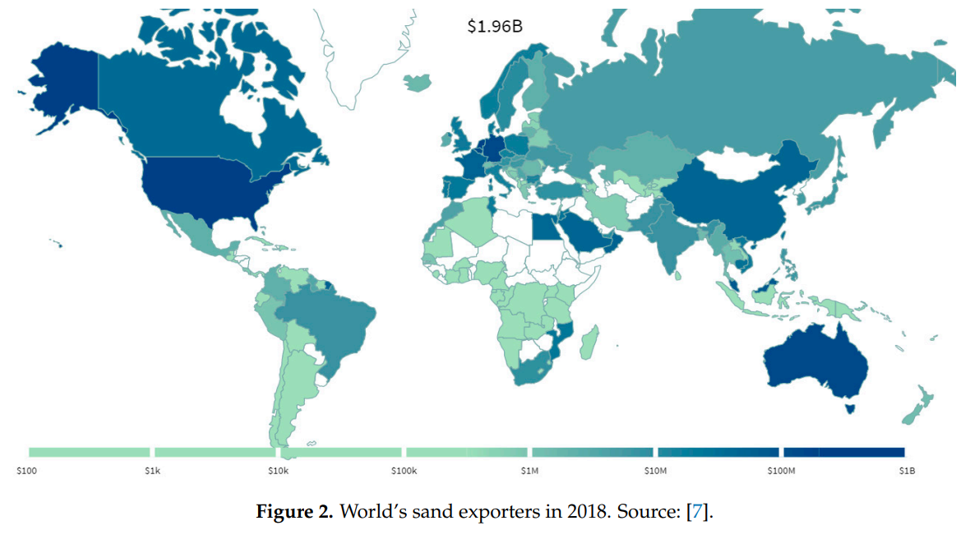

Additionally, urban expansion in places such as China, India, and many African countries drives the need for concrete, which can be cast quickly and is easily accessible. Unfortunately, the demand is too large and domestic mining cannot keep up. In response, the Global North massively exports sand, creating large financial opportunities for wealthy developed countries. As reported by World’s Top Exports,

In 2022, the world’s top 5 sand exporters [were] the United States of America, Netherlands, Germany, Belgium and Malaysia. Together, these 5 main exporters of sand were responsible for over three-fifths (62.5%) of the total value of natural sand shipped onto international markets… suppliers in Europe sold the highest dollar amount of exported sands during 2022 with shipments valued at $750.6 million or 41.6% of the global total. In second place were North American exporters generating 34% worth of sales while another 15.8% of worldwide sand shipments originated from Asia (Workman 2022)

Finally, as seen below, there is a constant exchange of sand between countries. Though wealthy countries sell lots of sand, they also import massive amounts, creating questions regarding the quality of exports as compared to what is imported.

Courtesy of Fliho et al.

The Hidden Effects

As of writing this, there is no international governing body which regulates sand mining and consumption. Developing countries where sand mining primarily occurs often do not have strict domestic regulations and are rampant with illegal sand mining. Currently, there are two primary types of illegal sand mining, one involves the removal of sand from restricted or protected areas and the other involves the removal of more sand that allowed by the local jurisdiction or authority. Protesters and activists in India, Bangladesh, and other southeast Asian countries have been severely hurt and killed due to these illegal sand miners, often referenced as “sand mafias”. In a report from the South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers, and People, it was found that, “at least 418 people have lost their lives while 434 have sustained injuries in sand mining related violence and accidents in India during December 2020 and March 2022.” (SANDRP 2022) Additionally, the poorest and most vulnerable citizens are impacted by being forced into employment due to poverty or driven to lash out against miners. A piece by Le Monde detailing the state of sand mining along the Son River in India reports, “For 400 rupees (about 5 euros) a day, [sand miners] worked at the foot of [a] sandy cliff that could have buried them at any moment… “I have no other option to feed my family,” said Bhugar Rai, 25. “If I don’t work here, we’ll all starve.”” Further, these rings of organized crime pay off politicians and law enforcement, allowing them to continually push the envelope on the issue. As written by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime,

A headman in Uttar Pradesh’s Gautam Buddh Nagar district, close to Delhi and a hive of sand mining activity, offers an interesting perspective on mafia–police relations. He claimed that the local sand mafia pays a monthly bribe of 50,000 rupees [about $600] to the police station and thereafter treats policemen as it wishes. This extends to beating up patrols that do not honor the ‘arrangement’ and try to stop mining activity (Mahadevan 2019, 17).

How Our Environments Suffer

Illegal mining further cements itself as a global concern when considering the environmental cost. In Asia, where mining limits are rarely enforced, illegal sand miners focus on regions like the Yangtze and Mekong River deltas, quickly degrading the surrounding environment (North and Whiting, 2023). The following photos show the Son River in Uttar Pradesh, India over a course of the past eight years. Even in a remote area where only one thousand people reside, sand mining is rampant.

Further environmental issues persist. As sand is removed, riverbeds become deeper, contributing to lower water levels. This lowered water table thus restricts farmers’ access to water for their crops. Simultaneously, salinization of fresh water occurs as salt is trapped by dams and deeper riverbeds (Esalmi 2021). Because of this, potable water for drinking and habitable waters for food such as fish or plants are eliminated. The elimination of food sources sequentially reduces opportunities for jobs such as fishing or boat sales and repairs, directly impacting coastal communities. Additionally, the spread of invasive species happens as organisms are transported on boats or mining vessels. This threatens local wildlife as invasive species can act as predators and take up crucial resources that help native wildlife thrive. Finally, changes in coastlines and the bodies of water around them contribute to stagnant waters where disease-carrying insects can breed, leaving populations vulnerable to malaria and other illnesses.

Further environmental issues persist. As sand is removed, riverbeds become deeper, contributing to lower water levels. This lowered water table thus restricts farmers’ access to water for their crops. Simultaneously, salinization of fresh water occurs as salt is trapped by dams and deeper riverbeds (Esalmi 2021). Because of this, potable water for drinking and habitable waters for food such as fish or plants are eliminated. The elimination of food sources sequentially reduces opportunities for jobs such as fishing or boat sales and repairs, directly impacting coastal communities. Additionally, the spread of invasive species happens as organisms are transported on boats or mining vessels. This threatens local wildlife as invasive species can act as predators and take up crucial resources that help native wildlife thrive. Finally, changes in coastlines and the bodies of water around them contribute to stagnant waters where disease-carrying insects can breed, leaving populations vulnerable to malaria and other illnesses.

Beyond the effects of mass removals of sand, the aftereffects of mining can be seen. By dredging sand, ships massively disrupt the floors of rivers and oceans. As written in Environmental Impacts of Sand Mining: A Comprehensive Review, “Sedimentation and turbidity resulting from mining activities impair water quality, reducing light penetration and oxygen levels, thereby disrupting aquatic ecosystems and compromising water supply for human consumption and irrigation” (Choudhary, Kansara, and Poonia 2024, 312). Reduced visibility not only hinders existing life but also eliminates thousands of organisms’ lives. This loss in biodiversity leaves the ecosystem exposed and susceptible to further damage.

Ultimately, each one of these issues result from increased mining, a response to the sand shortage. What should be done to combat the shortage itself?

Moving Beyond Sand

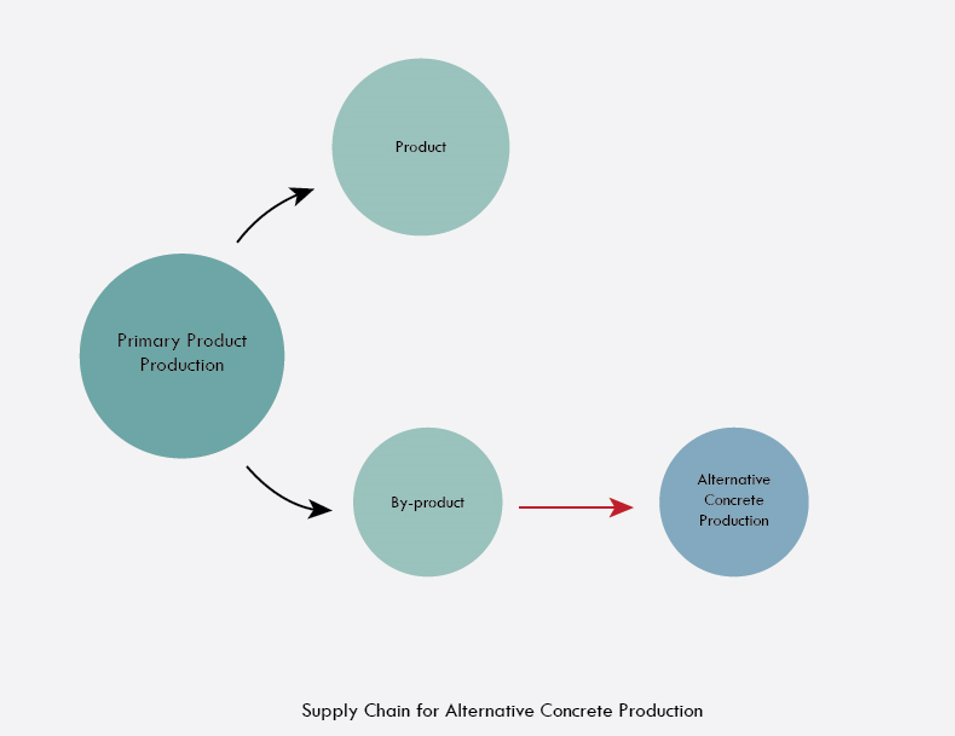

Because the shortage is centered specifically around river sand and thus concrete production, efforts have been made to find alternatives. Detailed extensively in “A review on alternatives to sand replacement and its effect on concrete properties”, by-product materials such as fly ash, steel slag, and ceramic waste are viable options to replace our reliance on sand when producing concrete. (Jagan et al. 2024, 2) Many of these substitutes increase strength in concrete, allowing less concrete to be used overall. Unfortunately, there is a drawback to this process. Using byproducts for alternative concretes creates reliance on the production of other goods. These by-products are not currently made in a cost-effective way separately from their original production methods. While helping to reduce waste from other manufacturing activities, this method is not fool proof for the future.

Then again, another possible solution is finding alternatives to not just sand but, to concrete completely. Many grassroots efforts have begun to find solutions to this on a small scale. For instance, a material called “Ferrock” is a product composed of steel shavings, silica (which is derived from ground glass), and ferrous rock.

Courtesy of Build Abroad

The product can be made with up to 95% recycled content and absorbs CO2 as it cures. It is also five times stronger than concrete and cures completely in one week. With reliance on byproducts, this is not a sustainable product in terms of long-term or large-scale production but is a powerful discovery in the construction world.

Additionally, hemp and mushrooms have become powerful biomaterials when developing alternatives to concrete. “Hemp-crete” is a combination of hemp shives, small pieces of the stalk, and lime or mud cement. These materials combine much like those of traditional concrete and can be pre-cast or cast-in-place. It takes advantage of a renewable material as well as a by-product of other manufacturing processes. This also serves as a carbon negative material, as hemp sequesters CO2 as it grows and retains it when turned into hempcrete.

Courtesy of IsoHemp Natural Building

Finally, we can divert usage by opting for alternative structure systems. Mass timber serves as an amazing alternative to concrete and has developed enough to support over 10 stories. Made of large pieces of cross-laminated timber (CLT) and glue-laminated wood, these wood members are assembled much like puzzle pieces. Because of this, assembly times are quick, less workers are required, and jobsite waste is reduced (Naturally Wood 2024). Finally, trees are an easily accessible resource, making mass timber a sustainable option for building construction that is not difficult to find or excessively expensive.

Courtesy of Waechter Architecture

Going Forward

In the end, without massive reform and huge changes in the global construction industry, we will continue to face a sand crisis. This issue permeates every level of the construction and architecture industry, creating a great responsibility for not only designers but everyone who makes decisions throughout a building’s design process. With many social, financial, and even political layers feeding into sand and concrete consumption, it is important to challenge the sand shortage with compassion and understanding while staying firm in the pursuit of preserving the sand the world has left. By reducing our reliance, searching for effective alternatives, and educating professionals across all industries, the unsustainable rate at which we consume sand can be lowered. With many firms and designers consciously acting to reduce their sand use, there is hope that the crisis can be beat. Going forward, it will become even more crucial to explore the nuances of this shortage such as its impact on agriculture, societies on both a small and large scale, and the layers of production for goods that utilize sand.

Author

Juliah Linzmeier is a Sustainability Student at Clark Nexsen for the summer of 2024. She is pursuing a Bachelor of Architecture and a minor in Sustainable Urban Planning at Virginia Tech with plans to graduate in the spring of 2026.

Bibliography

“Atelier Régis ROUDIL Architectes, 11H45 · Child Care Centre.” 2023. Divisare. 2023. https://divisare.com/projects/475613-atelier-regis-roudil-architectes-11h45-child-care-centre.

Barker, Nat. 2023. “Nine Buildings Constructed Using Hemp That Show the Biomaterial’s Potential.” Dezeen. January 6, 2023. https://www.dezeen.com/2023/01/06/hemp-hempcrete-buildings-architecture/.

Eslami, Sepehr. 2021. “Fifty per Cent of the Mekong Delta at Risk of Salinization due to Sand Mining and Dam Building – News – Utrecht University.” Www.uu.nl. July 15, 2021. https://www.uu.nl/en/news/fifty-per-cent-of-the-mekong-delta-at-risk-of-salinization-due-to-sand-mining-and-dam-building.

“Four Questions for Eric Lambin on the Sand Shortage.” 2022. Stanford.edu. Stanford University. 2022. https://news.stanford.edu/stories/2022/07/four-questions-eric-lambin-sand-shortage.

Hernandez, Marco, Simon Scarr, and Katy Daigle. 2021. “The Messy Business of Sand Mining.” Reuters, February 18, 2021. https://www.reuters.com/graphics/GLOBAL-ENVIRONMENT/SAND/ygdpzekyavw/.

Izat Hamakareem, Madeh. 2022. “What Is Ferrock in Construction?” The Constructor. July 25, 2022. https://theconstructor.org/concrete/ferrock-characteristics-applications/565525/.

Jagan, Inti, Pongunuru Naga Sowjanya, and Kanta Naga Rajesh. 2023. “A Review on Alternatives to Sand Replacement and Its Effect on Concrete Properties.” Materials Today: Proceedings, March. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.03.332.

Johnson, Chad. 2016. “Ferrock: A Stronger, Greener Alternative to Concrete?” Build Abroad. September 27, 2016. https://www.buildabroad.org/2016/09/27/ferrock/.

Leal Filho, Walter, Julian Hunt, Alexandros Lingos, Johannes Platje, Lara Werncke Vieira, Markus Will, and Marius Dan Gavriletea. 2021. “The Unsustainable Use of Sand: Reporting on a Global Problem.” Sustainability 13 (6): 3356. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063356.

“LEVER» Projects» Albina Yard.” n.d. Leverarchitecture.com. https://leverarchitecture.com/projects/albina_yard.

Mahadevan, Prem. 2019. “Disorganized Crime in a Growing Economy SAND MAFIAS in INDIA.” https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Sand-Mining-in-India-Report-17Jul1045-Web.pdf.

Manon. 2018. “Hemp Blocks for Naturally Efficient Masonry.” IsoHemp – Sustainable Building and Renovating with Hempcrete Blocks. February 14, 2018. https://www.isohemp.com/en/hemp-blocks-naturally-efficient-masonry.

“Mass Timber — Waechter Architecture.” 2014. Waechterarchitecture.com. 2014. https://waechterarchitecture.com/MASS-TIMBER.

Monjoy, Valeria. 2023. “What Is Steel Slag Concrete?” ArchDaily. January 26, 2023. https://www.archdaily.com/995470/what-is-steel-slag-concrete.

Mouterde, Perrine. 2022. “India’s ‘Sand Mafias Have Power, Money and Weapons.’” Le Monde.fr, September 12, 2022. https://www.lemonde.fr/en/environment/article/2022/09/12/in-india-sand-mafias-have-power-money-and-weapons_5996639_114.html.

Nasir, Osama. 2024. “From Fungi to Foundations: Mycelium in Construction.” Parametric Architecture. July 2, 2024. https://parametric-architecture.com/from-fungi-to-foundations-mycelium-in-construction/.

published, The Week Staff. 2023. “Why Is the World Running out of Sand?” Theweek. May 23, 2023. https://theweek.com/news/science-health/960931/why-is-the-world-running-out-of-sand.

Romig, Rollo. 2017. “How to Steal a River (Published 2017).” The New York Times, March 1, 2017, sec. Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/01/magazine/sand-mining-india-how-to-steal-a-river.html.

“Sand Mining | UNDRR.” 2023. Www.undrr.org. June 7, 2023. https://www.undrr.org/understanding-disaster-risk/terminology/hips/en0022.

Sandrp. 2022. “India Sand Mining: Violence & Accidents Killed 418 People in 16 Months.” SANDRP. April 24, 2022. https://sandrp.in/2022/04/24/india-sand-mining-violence-accidents-killed-418-people-in-16-months/.

Schires, Megan . 2021. “Hempcrete: Creating Holistic Sustainability with Plant-Based Building Materials.” ArchDaily. April 15, 2021. https://www.archdaily.com/955176/hempcrete-creating-holistic-sustainability-with-plant-based-building-materials.

Somvanshi, Avikal . 2013. “Concrete without Sand?” Www.downtoearth.org.in. August 4, 2013. https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/concrete-without-sand-41849.

Souza, Eduardo. 2022. “Concrete Jungles: 6 Cement Alternatives That Can Reduce Its Impact in Cities.” ArchDaily. July 26, 2022. https://www.archdaily.com/985952/concrete-jungles-6-cement-alternatives-that-can-reduce-its-impact-in-cities?ad_source=search&ad_medium=projects_tab&ad_source=search&ad_medium=search_result_all.

Torres, Aurora, Jodi Brandt, Kristen Lear, and Jianguo Liu. 2017. “A Looming Tragedy of the Sand Commons.” Science 357 (6355): 970–71. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao0503.

UNEP. 2022. “Sand and Sustainability: 10 Strategic Recommendations to Avert a Crisis.” UNEP – UN Environment Programme, April 25, 2022. https://www.unep.org/resources/report/sand-and-sustainability-10-strategic-recommendations-avert-crisis.

Whiting, Kate, and Madeleine North. 2023. “Sand Mining Is close to Being an Environmental Crisis. Here’s Why – and What Can Be Done about It.” World Economic Forum. September 21, 2023. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/09/global-sand-mining-demand-impacting-environment/.

Wikipedia Contributors. 2024. “Sand.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. May 13, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sand#:~:text=Rocks%20erode%20or%20weather%20over.