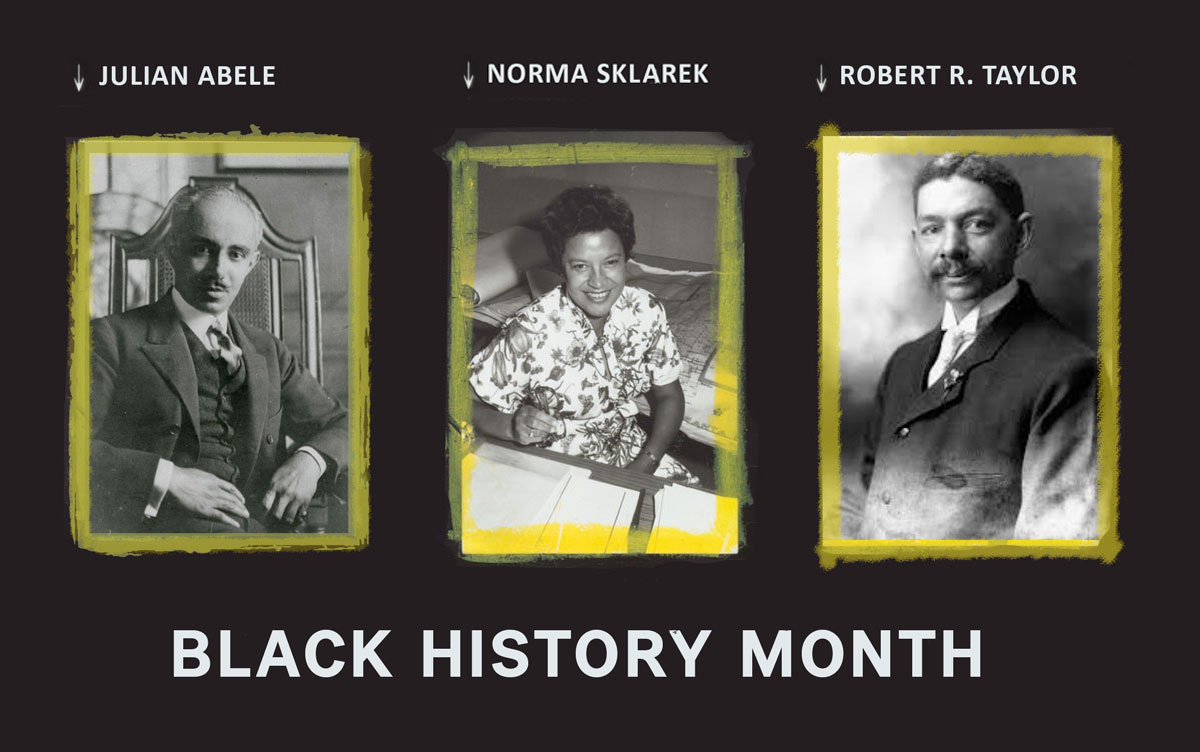

Clark Nexsen Celebrates Black History Month

To celebrate Black History Month across our offices, our professionals are honoring members of the Black community who have impacted or inspired them. Here are the remarkable stories of three Black architects they want to elevate:

w

Architect Julian Abele, AIA, designed the iconic Duke University Chapel as well as more than 30 additional campus buildings between 1924 and 1950.

Julian Abele, AIA (1881–1950)

Until protests against the apartheid in South Africa took place on Duke University’s campus in 1986, it was largely unknown that Abele had designed much of Duke University’s renowned neo-Gothic west campus from 1924–1954 (his designs were still under design/construction at the time of his passing). Abele’s great grandniece Susan Cook, who was a sophomore at the university, revealed that Julian Abele had designed the Duke University Chapel, library, Wallace Wade Stadium, Cameron Indoor Stadium, medical school, religion school, hospital and facility houses. Yet, he “was a victim of apartheid in this country,” as said by Cook. Due to racist Jim Crow laws, Abele was never allowed to set foot on the campus of Duke University.

“Meet the Black architect who designed Duke University 37 years before he could have attended it. His name was Julian Abele.” — Rachel B. Doyle

Julian Abele graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1902 as the first Black student to go through the architecture program. He went on to contribute to the design of over 400 buildings. During his career, he was rejected from the AIA for 10 years until being elected to membership in 1941 – only 9 years before his passing. In 2016, Abele’s role in the shaping of Duke’s campus was honored with the renaming and dedication of the West Campus quad to the “Abele Quad.”

Shared by Zakiya Wiggins, Associate AIA – Raleigh

w

While a director at Gruen Associates, Sklarek collaborated with César Pelli on a number of projects, including (left to right) the Pacific Design Center in Los Angeles, Fox Plaza in San Francisco, and Santa Monica Place.

Norma Sklarek, FAIA (1926–2012)

Once called “the Rosa Parks of architecture” by AIA board member Anthony Costello, Harlem-born Norma Merrick Sklarek overcame racism and sexism to become the first licensed black female architect in New York in 1954, the first black female member of the AIA in 1959, the first licensed black female architect in California in 1962, the first black female Fellow of the AIA in 1980, and cofounder of the nation’s largest woman-owned architecture firm (Siegel Sklarek Diamond) and the first black woman to co-own an architecture firm in 1985.

“Architecture should be working on improving the environment of people in their homes, in their places of work, and their places of recreation,” Sklarek said of the practice. “It should be functional and pleasant, not just in the image of the ego of the architect.”

As an architecture student at Barnard College and Columbia University, she was one of two women and the only black student in her 1950 class, and upon graduation was passed over for several jobs (“They weren’t hiring women or African Americans, and I didn’t know which it was [working against me],” she is quoted as saying to a local newspaper) until she landed a role with the Department of Public Services, then at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, and then Gruen Associates in Los Angeles. She collaborated often with César Pelli on iconic structures such as the Pacific Design Center and the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo, before cofounding her own practice with Margot Siegel and Katherine Diamond.

Shared by Breanna Hegamin, Marketing Coordinator – Virginia Beach

w

Left: Robert R. Taylor designed White Hall at the Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama, completed in 1910. Photo by Justin Dubois. Right: Prince Hall Masonic Temple in Birmingham, Alabama, a Renaissance-Revival-style building completed in 1922. Robert R. Taylor designed the building in collaboration with his former Tuskegee student, Leo Persley – both were the state’s only two professional black architects at the time.

Robert R. Taylor (1868 – 1942)

w

As a kid riding my bike through historic Oakdale Cemetery in Wilmington, NC I found the imposing gravesite monument of Henry Bacon, with Architect of the Lincoln Memorial inscribed on it. For all the years since, I believed he was the most significant architect who came from my hometown. But recently I discovered there was another Wilmington architect, Robert Robinson Taylor, who should have been revered as much for his accomplishments, if not more so, as Henry Bacon.

The son of a freed slave who was a carpenter, Taylor became the first African American student enrolled at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and first accredited Black architect in the country when he graduated in 1892.

While at MIT, Taylor met Booker T. Washington, which led to his joining him at Tuskegee Institute, founded by Washington. Washington was looking for talented Black students to join him in leadership roles at Tuskegee and saw in Taylor someone who could plan and direct the construction of future buildings on campus. Construction teams typically included students, many also descendants of slaves, to learn the means of the building trades. Taylor designed and built structures on the Tuskegee campus for 40 years, as well as significant buildings at other historically Black colleges and universities in the South. He died in 1942, after attending services at the Tuskegee Chapel, a structure he considered his outstanding achievement as an architect. Taylor’s great-granddaughter is Valerie Jarrett, former senior advisor to President Obama.

If I had ridden my bike into the neighboring cemetery to Oakdale, hidden behind trees and hard to find, I might have come upon Robert Taylor’s resting place in Wilmington’s “cemetery for colored residents” (from the plaque at the entrance). If his grave monument isn’t the equal to Bacon’s, it should be.

Shared by Kevin Utsey, FAIA – Charlotte